| Issue |

Natl Sci Open

Volume 4, Number 6, 2025

Special Topic: Intelligent Materials and Devices

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 20250046 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Materials Science | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1360/nso/20250046 | |

| Published online | 29 October 2025 | |

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Multi-scale regulation of structure and material for visible-infrared-LiDAR multispectral camouflage

1

College of Sciences, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410073, China

2

College of Physics and Optoelectronic Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China

3

School of Physical Science and Technology, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China

* Corresponding authors (emails: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

(Zhaojian Zhang); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

(Huan Chen); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

(Junbo Yang))

Received:

12

September

2025

Revised:

25

October

2025

Accepted:

27

October

2025

The development of detection technologies has driven an urgent need for multispectral camouflage capabilities. However, the requirement for multispectral camouflage, including colored visible (VIS) camouflage, adaptive infrared camouflage, and multi-band light detection and ranging (LiDAR) camouflage, challenges conventional single-design approaches from design to fabrication. Here, we propose a simplified design strategy that enables decoupling between material and structural regulation, thereby enhancing multiband modulation performance. From visible to near-infrared (NIR) bands, thin-film Fabry-Pérot cavities facilitate simultaneous visible structural color and NIR laser band absorption. The calculated VIS results are in excellent concordance with experimental ones (∆Ē < 6). Experimental measurements further demonstrate broadband (900–1550 nm) ultra-high absorption (A > 90%) in the NIR band. The orders-of-magnitude difference in wavelengths enables structural dimensions decoupling, effectively separating the influence of the architecture on visible and mid-infrared (MIR) performance. In the MIR region, the metadevice realizes adaptive infrared thermal camouflage (Δε8–14 μm = 0.46) with LiDAR camouflage based on phase-change material. Especially, the peak absorption reaches 99.2% near the wavelength of 10.6 μm (A10.6 μm = 92.1%). Moreover, the metadevice exhibits independent triple-band display including VIS, laser and MIR bands. Our study provides a theoretical framework for multi-scale optical modulation and demonstrates broad potential for applications in multispectral camouflage, multi-band displays, information encryption, and radiative cooling.

Key words: phase change materials / visible / infrared camouflage / display / encryption

© The Author(s) 2025. Published by Science Press and EDP Sciences.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

INTRODUCTION

Multispectral manipulation technology seeks to achieve electromagnetic waves regulation covering multiple orders of magnitude in wavelength [1–4]. This capability creates new opportunities for optoelectronic devices and promises broad applications across science and technology, such as materials science [5–7], thermodynamics [8–10], information science [11,12], and military applications [13–15]. In particular, military applications increasingly rely on detection systems that combine multiple spectral sensing modalities—including visible surveillance, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), and infrared (IR) thermal imaging [16–18]. The evolution of multispectral detection methods introduces significant new challenges for visible-infrared-LiDAR (VIS-IR-LiDAR) multispectral camouflage technologies [19].

Recently, multispectral camouflage has increasingly concentrated on optical structure design to achieve desired performance. Cho et al. [20] developed layered metamaterials capable of simultaneous infrared and microwave camouflage. Hahn et al. [21] utilized a metal-semiconductor-metal (MSM) metamaterial to integrate visible and infrared camouflage functionalities. Nevertheless, the widespread adoption of such micro- and nanostructures is hampered by complexities in fabrication. In addition, multispectral strategies constrained by structural limitations lack adaptability in complex and varied environments. Meanwhile, material-based approaches have shown enhanced versatility in multispectral manipulation. Kocabas et al. [22] introduced a graphene-based optoelectronic platform that supports multispectral modulation from visible to microwave frequencies. Li et al. [23] demonstrated multispectral manipulation in the visible and microwave ranges using vanadium dioxide (VO2). However, the uniformity of the modulating material results in simultaneous response across the entire spectrum, which restricts its applicability in camouflage and display technologies. Thus, neither a single structural approach nor a standalone material method can meet the growing demand for multispectral modulation.

In our previous work [24], independent bicolor infrared regulation was demonstrated successfully using a hybrid of multiple phase-change materials, including VO2, Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST), and In3SbTe2. However, systematic investigation into band-extended functionality has remained scarce. Here, we introduce a simplified design strategy based on multi-scale structural and material manipulation to achieve multispectral compatibility across VIS, IR, and LiDAR camouflage bands. Based on the nonvolatility of GST [25] and the wide bandgap characteristics of ZnS [26], a multilayer thin-film structure composed of ZnS/GST/Cr was designed and fabricated. Leveraging thin-film architectures with distinct dimensional features, wavelength-selective regulation was effectively realized. By examining the spectral sensitivity of the materials, we elucidated the underlying mechanism behind band-specific modulation. The proposed metadevice exhibits several key advantages: rich structural color in the visible spectrum, ultrabroadband (~650 nm) and high-performance continuous absorption (A > 90%) in the near-infrared (NIR) region, and high modulation (Δε8–14 μm = 0.46) of infrared emissivity together with high-performance absorption (A10.6 μm = 92.1%) at 10.6 μm in the mid-infrared (MIR) band. Additionally, the device demonstrates independent information display capacity across different bands—VIS, NIR, and MIR—each revealing distinct patterns. This work establishes a new theoretical framework for multispectral modulation and suggests promising potential in multispectral camouflage, radiative cooling, and advanced display technologies.

DISCUSSION

Fundamental design

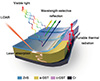

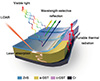

The essential criteria for VIS-IR-LiDAR multispectral camouflage technology include: (1) tunable color presentation within the VIS band; (2) strong and broadband absorption in the NIR region to suppress laser reflection; (3) adaptive MIR emissivity coupled with high laser absorption at 10.6 μm. To address these requirements, the fundamental concept of multi-scale regulation based on combined material and structural design is introduced. As illustrated in Figure 1, we designed a simplified optical metadevice, comprising a tri-layer configuration of ZnS, GST, and Cr. Multispectral compatibility is achieved via structural modulation and coordinated material across different scales. Specifically, the ZnS layer provides optical characteristics suitable from the VIS to NIR bands, while the GST layer of offers functionality within the MIR band. A sufficiently thick Cr layer serves as a reflective mirror, effectively blocking back propagation of electromagnetic wave across multiple spectral bands.

|

Figure 1 The schematic of VIS-IR-LiDAR multispectral camouflage realized by simplified design for multi-scale regulation of structure and material. |

Conventional single-target designs face considerable difficulty in concurrently controlling both visible and MIR spectral properties, as this necessitates two decoupled modulation mechanisms. Some researchers have predominantly focused on single band modulation that targets one spectral band while maintaining the other steady-state conditions, such as transparent thermal radiation modulation [27,28], microwave scattering with thermal modulation [29], and colored radiative cooling [30,31]. The orders-of-magnitude difference in wavelengths between the visible and infrared regimes allows metamaterials to manipulate these bands independently [32]. Specifically, adjusting the thickness of the top dielectric layer enables modulation of visible and NIR reflectance, facilitating both vivid structural color formation and broadband ultra-high absorption in the NIR band. The reduction of reflectivity effectively suppresses laser echo signals, enhancing evasion against laser detection. Additionally, an optical microcavity composed of a GST layer with a thickness matching the MIR resonance and a metal mirror allows for precise modulation of MIR emissivity and highly efficient absorption within the MIR laser band.

VIS-NIR regulation technology

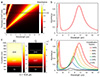

As a typical wide-bandgap material, ZnS exhibits high transparency across the VIS, NIR, and MIR regions [26]. Within the VIS to NIR range, varying the thickness of ZnS modulates the phase of light transmission and reflection, thereby shifting the resonance peak positions in the visible spectrum. To achieve a diverse structural color palette, the visible reflectance spectra of a single-layer ZnS film were analyzed (Figure 2a). The corresponding spectral data for these variations in thicknesses (10 to 300 nm) were then converted into the CIE1931 chromaticity diagram (Figure 2b) [15]. The details of the relationship between the VIS reflectance spectrum and perceived color are discussed in Supplementary Note 1. Subsequently, ZnS layers with thicknesses of 65, 85, 120, 145, 180, and 240 nm were deposited on a GST/Au layer, as illustrated in Figure 2c. The position of the experimental results is also marked by stars in Figure 2b. Theoretical results indicate that varying the thickness enables coverage of most target colors. Furthermore, experimental results show good agreement with theoretically simulated visible spectra as presented in Figure 2d, with the average color difference ({L-End}

) between experimental and theoretical Commission International del’Eclairage (CIE) values being less than 6 (see Supplementary Note S1 and Figure S1).

) between experimental and theoretical Commission International del’Eclairage (CIE) values being less than 6 (see Supplementary Note S1 and Figure S1).

|

Figure 2 (a) Optical transmission behavior in thin-film structure. (b) Color range and distribution of designed and experimental structure in CIE 1931 color space. (c) Photographs showcasing the fabricated structures with different thicknesses (NO.1: 65 nm; NO.2: 85 nm; NO.3: 120 nm; NO.4: 145 nm; NO.5: 180 nm; NO.6: 240 nm). (d) Experimental (Exp., solid line) and simulated (Sim., dotted line) reflectivity spectra of six structures within the visible waveband with color difference ({L-End}

|

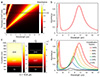

The multi-order interference peaks generated by ZnS are nearly equally spaced in frequency from VIS to NIR bands. As a result, resonance peaks in the lower frequency region (NIR) exhibit broader bandwidth compared to those at higher frequencies (VIS). Experimental measurements for different thicknesses of the ZnS layer, under crystalline GST (c-GST) and amorphous GST (a-GST) interlayers respectively, are presented in Figure 3a, b. At a ZnS layer thickness of 120 nm, the metadevice achieves a low-reflectance (R < 20%) bandwidth of up to 830 nm in the NIR range, incorporating outstanding absorption performance at key laser wavelengths (A905 nm = 87.7%, A1064 nm = 98.6%, A1310 nm = 97.6%, A1550 nm = 90.1%). This high absorption effectively minimizes laser echo, significantly reducing the risk of LiDAR detection. However, increasing the ZnS thickness gradually degrades the broadband characteristic due to the emergence of additional interference peaks within the same band that satisfy interference conditions.

|

Figure 3 Reflectance spectra with different thicknesses of ZnS layer under crystalline (a) and amorphous (b) GST interlayers. (c) Electric field distribution of designed structure (NO.3) with marked skin depths at the resonant wavelength of 428 and 1064 nm. (d) Loss distribution of designed structure (NO.3) at the resonant wavelength. |

Notably, the influence of GST thickness on the resonant cavity has not been addressed in this analysis, as GST functions as an absorbing material throughout the visible to NIR range, regardless of its crystalline or amorphous state. As a result, the GST-Cr interface does not participate in the reflection of VIS-NIR light. To elucidate this behavior, the electric field distributions at the VIS (λ = 428 nm) and NIR (λ = 1064 nm) resonance peaks are provided in Figure 3c for the proposed metadevice with a ZnS layer size of 120 nm. It is evident that the electric field does not propagate to the GST-Cr interface. Within this cavity, the skin depths of electric field intensity at both the VIS and NIR resonance peaks are approximately 20 and 40 nm, as marked in Figure 3c. The loss of electric fields in opaque media can be expressed by the impedance Joule heating law [33,34].

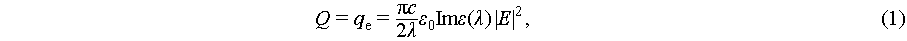

where c is the light velocity in a vacuum, λ is the target wavelength, ε0 and ε are the vacuum permittivity and the material permittivity, and E is the intensity of the electric field.

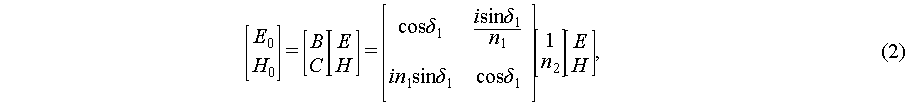

Therefore, the thin-film structure can be considered effectively as a ZnS layer with a GST substrate in the VIS and NIR bands. This phenomenon can be analyzed further using the transmission matrix method. Since the electric field is impermeable, the matrix takes the form as [35,36]

where n1 and n2 correspond to the refractive indices of ZnS and GST, respectively, δ1 represents the transmission phase provided by the ZnS layer, and {L-End}

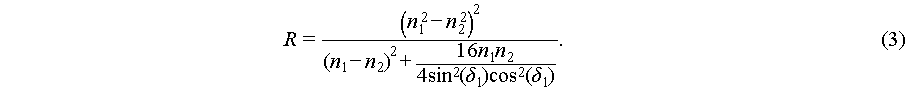

. Reflectance can be expressed as

. Reflectance can be expressed as

As indicated by Eq. (3), the resonance peak position depends exclusively on the transmission phase (δ1) introduced by the ZnS layer thickness and remains unaffected by variations in either the thickness or state of GST. To validate this finding, the experimental reflection spectrum under different states of GST was examined (Figure S2). The results confirm that the interference peak location is determined solely by the ZnS thickness, thereby corroborating the effectiveness of the configuration presented in Figure 2a.

The decoupling phenomenon between the VIS-NIR and MIR bands is attributed to the spectral sensitivity of the materials. Specifically, high-frequency (VIS-NIR) photons are subjected to interference effects localized solely in the ZnS layer with ultra-thin skin depths in the GST layer. Conversely, low-frequency (MIR) electromagnetic wave, possessing loss propagation, interact with the underlying metal mirror (Cr). In this scenario, the loss which is governed by the state of the GST layer, is pivotal for tailoring the spectral behavior in the MIR band. Given that the optical responses in the high- and low-frequency regions are governed by structure and material, they can be treated as decoupled modulation.

Mid-infrared band regulation technology

The MIR region can be modulated via the GST material, enabling multi-scale manipulation. To achieve tunable emissivity, a resonator composed of crystalline GST and Au was utilized for MIR absorption. The broadband properties of ZnS allow it to introduce a transmission phase in the MIR region. A predetermined ZnS thickness applied in simulations offers MIR phase compensation. Figure 4a illustrates the relationship between the thickness of c-GST and the MIR emission spectrum with a fixed ZnS thickness of 120 nm. The calculated results show that increasing the GST film thickness causes a red shift in the resonant peak of the MIR cavity mode. To maximize absorption at the wavelength of 10.6 μm, the thickness of the GST layer was optimized to 420 nm. Figure 4b shows the absorption spectra for the ZnS/GST/Cr multilayer structure with thicknesses of 120, 420, and 200 nm, respectively. The result demonstrates the high performance of the proposed metadevice for MIR LiDAR camouflage (A10.6 μm = 92%). Figure 4c demonstrates that the electric field distribution achieves ideal reflection phase matching at the resonant wavelength of 10.6 μm for the combined 120 nm ZnS and 420 nm GST layers. According to Eq. (1), the electromagnetic loss distribution at the resonant wavelength of 10.6 μm confirms strong energy localization within the GST layers owing to interference effects. The synergistic absorption effect between the GST and Cr layers is responsible for the perfect absorption. The slight shift of the MIR resonance peak due to different transmission phase caused by changes in ZnS thickness is further analyzed (Figure S3). Additionally, adaptive thermal camouflage realized by modulating the phase state of GST [37] enables effective manipulation over MIR emissivity as shown in Figure 4d, which can theoretically be tuned from 0.1 to 0.7.

|

Figure 4 (a) Absorbance spectrum with different thicknesses of GST layer under crystalline state. (b) The calculated absorbance spectrum of the proposed metadevice. (c) Electric field distribution (left) and loss distribution (right) of designed structure at the resonant wavelength (10.6 μm). (d) Realization of adaptive thermal camouflage by modulating the phase state of GST. |

As a key indicator of multiband compatible camouflage, the calculated absorptivity versus wavelength and incident angle (0°–80°) for the P- and S-polarized light is shown in Figure S4. With high angle incident light (60°), the metadevice with c-GST exhibit robust performance including high peak absorption average LWIR emission. With the P-polarized light and the S-polarized light incidence, the device demonstrates the peak LWIR absorptivity in the LWIR band exceeding 80%.

The proposed metadevice of ZnS/GST/Cr with respective thicknesses of 120, 420, and 400 nm was fabricated as shown in Figure 5a. The modulation process in the MIR reflectance spectrum of the proposed metadevice under different heating steady-state temperatures is shown in Figure 5b. Owing to the sufficient thickness of the Cr layer to prevent IR transmission, the absorption at specific wavelengths can be given by reflectance measurements. The experimental results demonstrate a maximum long-wave infrared (LWIR, 8–14 μm) emissivity of 88%, an LWIR modulation depth of 0.46, and a peak absorption of 99.2% at the CO2 laser wavelength. Figure 5c records the evolution of both LWIR emissivity and absorption at 10.6 μm that was monitored throughout the thermal process. The modulation onset is observed at 125 °C and reaches completion at 160 °C.

|

Figure 5 (a) SEM photograph of the fabricated metadevice. (b) The measured reflectance spectrum of the proposed metadevice with different stable heating temperatures. (c) Recording emittance (absorbance) of average emissivity in the LWIR band and CO2 laser wavelength of 10.6 μm. (d) Relationship between heat temperature and observed temperature with reference of grey-body with average emission of 0.3 and 0.9, respectively. (e) Outdoor analysis of observed temperature with versus heating temperature and average emission. |

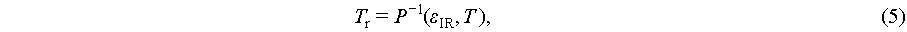

According to Planck’s blackbody radiation law, the apparent radiant power of an object can be expressed as the sum of its own emitted electromagnetic energy and the reflected background radiation electromagnetic energy [38]:

where εd and εa represent the emissivity of the device and the background emissivity, respectively, Td and Ta denote the device temperature and background temperature. Thermal imaging of a detector can be understood as the inverse temperature calculation of the received radiant energy through the blackbody radiation law.

where εIR is the emissivity within the detector’s operational wavelength range and εIR = 1 under normal circumstances. Figure 5d shows the experimental performance of the proposed metadevice in both crystalline and amorphous states of GST under indoor conditions with a background temperature of 25 °C. Emissivity reference curves of 0.3 and 0.9 are also included as dashed lines for comparison. Remarkably, at 90 °C, the maximum apparent temperature difference based on material phase transition regulation reaches 27 °C. These findings further demonstrate the potential of the metadevice for adaptive infrared camouflage applications.

Then, we analyze the relationship between apparent temperature and device temperature under clear, cloudless outdoor conditions. According to radiation cooling theory, the energy contribution from the cold-space background at 3 K can be neglected (Pref ≈ 0). Figure 5e reveals the relationship among apparent temperature, heating temperature, and emissivity under outdoor conditions. It can be seen that achieving adaptive infrared camouflage requires effective responses to different temperature scenarios. As shown by the red curve in Figure 5e, for a 60 °C object to achieve thermal camouflage against a 30 °C background blackbody reference in an outdoor environment, its emissivity should be 0.7.

Performance evaluation

To evaluate the VIS and IR camouflage performance of the proposed metadevice, both various types of natural leaves and the fabricated metadevice were observed under an optical camera and a thermal imager. As shown in Figure 6a, the metadevice mimics the color of natural leaves in the visible spectrum through adjustments in the top-layer thickness. Meanwhile, Figure 6b reveals that the metadevice and leaves exhibit closely matched apparent temperatures in thermal images, with a temperature difference below 1 °C. In contrast, human skin, a nearly ideal blackbody emitter, displays an apparent temperature consistent with its actual temperature.

|

Figure 6 (a) VIS camouflage evaluation and (b) MIR thermal camouflage evaluation of the proposed metadevice (NO.4 and NO.6) with references of different kinds of leaves. (c, d) LiDAR camouflage evaluation of the proposed metadevice for the different wavelengthes of 1.06 μm (NO.3 and without ZnS layer sample) and 10.6 μm (NO.5 with a-GST and c-GST). (e) Multispectral display with different bands version of VIS camera, laser detection, and MIR thermal camera. |

To evaluate the LiDAR camouflage performance of the proposed metadevice, reflectance measurements were conducted under varying irradiation power levels using a dual-band infrared laser transmittance-reflectance power correlation measurement system [19]. As illustrated in Figure 6c, the metadevice exhibits significantly enhanced laser absorption (93.7%) with laser reflectance reduced to 8.85% (a 10.5 dB reduction) compared to the GST/Au structure without a ZnS matching layer. Furthermore, the modulation of MIR laser absorption between the crystalline and amorphous states was examined. Figure 6d reveals that the absorption of the CO2 MIR laser can be tuned over a range of 2–15 dB (corresponding to 3%–62.5% absorption). The metadevice with c-GST achieves record-high MIR absorption capacity—surpassing that of quartz (Figure S5), resulting in significantly reduced reflectance at a wavelength of 10.6 μm. As shown in Table S1, the proposed metadevice shows superiority in meeting certain requirements including VIS camouflage, LiDAR camouflage, and MIR camouflage and advantage in minimizing layer number.

We further investigate the application of the metadevice for multispectral display functions, as shown in Figure 6e. A metadevice featuring “wolf” and “star” patterns was fabricated, with an 85 nm-thick ZnS film serving as the background (NO.2). The “star” (NO.3) and “wolf” patterns were realized using ZnS layers with thicknesses of 120 and 205 nm, respectively. The sample was characterized using a VIS camera, active NIR detection, and an MIR thermal camera. The “star” pattern displays strong contrast in the VIS range (CIE1931: Blue (0.30, 0.34), Yellow (0.41, 0.46)), while showing a reflectance of only 6% similar to the background in the NIR and demonstrating lower reflectance behavior. On the contrary, the “wolf” pattern exhibits a blue hue consistent with the background within the VIS range, but strong contrast in the NIR band (“wolf” pattern, R1064 nm = 25%). Additionally, under infrared thermal imaging, these patterned features of the proposed metadevice remain expectedly undetectable, due to the uniformly low emissivity of the device with a-GST layer, which causes their thermal signature to blend seamlessly into the background. Comparing with the state-of-the-art wavelength-division multiplexing displays (Table S2), our metadevice shows significant improvements in multi-band compatibility including VIS, NIR, and MIR.

CONCLUSIONS

This research demonstrates a successful implementation of multi-scale structure-material co-design to achieve multifunctional compatibility across VIS, NIR, and MIR bands. A ZnS/GST/Cr multilayer thin-film metadevice was developed to enable tunable structural color presentation in the VIS region, broadband high absorption in the NIR spectrum for laser echo suppression, and dynamically switchable infrared emissivity via the GST phase transition, together with high laser absorption in the MIR band. Experimental results demonstrate outstanding performance in VIS-IR-LiDAR camouflage and wavelength-selective independent display. The proposed strategy offers a viable pathway toward overcoming the challenges of multispectral camouflage and adaptive display integration, with promising applications extending beyond military camouflage to future intelligent optical systems, thermal management coatings, energy-efficient displays, and multisensory compatible devices.

METHOD

Simulations

The VIS-IR spectra under normal unpolarized incidence were simulated using the commercial software FDTD Solutions (Lumerical Solutions, Canada) with 2D model. The 2D VIS-IR plane waves propagated to the proposed device along the yz-direction. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in x-directions. The upper and lower boundary conditions in the z-direction perfectly matched layers, and the mesh size was 1 nm. The IR absorbance (A) spectra were obtained using the transmittance (T) and reflectance (R) as A = 1 − R − T. The refractive indices of GST were obtained from previous studies [39]. The optical constants of ZnS and Cr were available in the handbook by Palik [40]. The effective medium theories (EMT) were used to model the continuous state of VO2 from a dielectric-like state to a metallic state and were described as [37]

The effective permittivity εEMT represents the intermediate state of GST; while ε1 and ε2 denote the permittivity of a-GST and c-GST, respectively. The constant C represents the metallic fraction of c-GST and ranges from 0 to 1.

Fabrications

The proposed devices were fabricated on a single side-polished <100> crystalline silicon substrates. Electron beam evaporation was used to prepare the film coating of ZnS and Cr under a vacuum chamber pressure of 5 × 10−4 Pa. The deposition speeds of ZnS and Cr were 0.5 and 1 nm/s, respectively. The GST layer of the proposed metadevice was deposited using a magnetron sputtering system (Nordiko). The GST stoichiometric targets had a high purity of 99.99%.

Optical measurements

The VIS-NIR reflectance spectra were characterized by a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U4100) in the working band of 0.3 to 2.5 μm. A diffuse-reflectance integrating sphere made of polytetrafluoroethylene was used as the reflection reference.

The MIR reflectance and transmittance spectra were acquired by a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) micro-area spectrometer (Nicolet Continuum) and a mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) detector with liquid nitrogen cooling in the wavelength range of 2.5–15 μm.

The LWIR images were recorded using IR cameras operating in the range 7.5–14 μm (Guide PS600, with emittances of 1). The room temperature was maintained at approximately 25 °C.

Data availability

The original data are available from corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Hexiu Xu (Air Force Engineering University) for the helpful discussion. We gratefully thank Yifei Xiao (Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology) for her help with the schematics of the configurations.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFF0706005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12272407, 62275269, 62275271 and 62305387), the Foundation of National University of Defense Technology (NUDT) (ZK23-03), and the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2022JJ40552 and 2023JJ40683).

Author contributions

J.Y. and X.J. conceived the idea and made further innovations. J.Y. supervised the work and guided the project. X.J., J.N. and W.Y. did the experiments and characterizations. X.L., J.Z., X.Y.L., Q.J. and J.Z. performed some experiments. J.N. and X.J. wrote the manuscript. J.W., X.H., P.Y., H.C., Z.Z and S.H. modified the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information

Supplementary file provided by the authors. Access here

References

- Cheng C, Liu J, Wang F, et al. Photonic structures in multispectral camouflage: From static to dynamic technologies. Mater Today 2025; 85: 253-281. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Tan S, Zhao Y, et al. Broadband multispectral compatible absorbers for radar, infrared and visible stealth application. Prog Mater Sci 2023; 135: 101088. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Guo C, Li W, et al. Thermal photonics with broken symmetries. eLight 2022; 2: 25. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R, Xi W, Liu Y, et al. Thermal camouflaging metamaterials. Mater Today 2021; 45: 120-141. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Xie P, Wan H, et al. Ultrathin MXene assemblies approach the intrinsic absorption limit in the 0.5–10 THz band. Nat Photon 2023; 17: 622-628. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Ji M, Yi H, et al. Pushing the thinness limit of silver films for flexible optoelectronic devices via ion-beam thinning-back process. Nat Commun 2024; 15: 2248. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ho-Baillie AWY, Sullivan HGJ, Bannerman TA, et al. Deployment opportunities for space photovoltaics and the prospects for perovskite solar cells. Adv Mater Technologies 2022; 7: 2101059. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li W, Han T, et al. Transforming heat transfer with thermal metamaterials and devices. Nat Rev Mater 2021; 6: 488-507. [Article] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Song J, Zhao W, et al. Dynamic thermal camouflage via a liquid-crystal-based radiative metasurface. Nanophotonics 2020; 9: 855-863. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Huang S, Hu R. Adaptive radiative thermal camouflage via synchronous heat conduction. Chin Phys Lett 2021; 38: 010502. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yu F, Chen J, et al. Continuous-spectrum-polarization recombinant optical encryption with a dielectric metasurface. Adv Mater 2023; 35: 2304161. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Huang X, Ju Z, et al. A triband metasurface covering visible, midwave infrared, and long-wave infrared for optical security. Nano Lett 2025; 25: 4459-4466. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Franklin D, Cozart J, et al. Adaptive multispectral infrared camouflage. ACS Photonics 2018; 5: 4513-4519. [Article] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R, Zhu H, Qin B, et al. Digital camouflage encompassing optical hyperspectra and thermal infrared-terahertz-microwave tri-bands. Nat Commun 2025; 16: 8112. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xi W, Lee YJ, Yu S, et al. Ultrahigh-efficient material informatics inverse design of thermal metamaterials for visible-infrared-compatible camouflage. Nat Commun 2023; 14: 4694. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Dixit A. Nanotechnology for Defence Applications. Singapore: Springer, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhu H, Zhou Y, et al. Adaptive visible-infrared camouflage with wide-range radiation control for extreme ambient temperatures. PhotoniX 2025; 6: 25. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang C, Zhang L, et al. A dual-mode LiDAR system enabled by mechanically tunable hybrid cascaded metasurfaces. Light Sci Appl 2025; 14: 287. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Nong J, Li X, et al. Laser-adaptive inverse-design metamaterials for durable regulation from visible-infrared-lidar compatible camouflage to optical limiter. Laser Photo Rev 2025; e00883. [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Bae J, Lee N, et al. Hierarchical metamaterials for multispectral camouflage of infrared and microwaves. Adv Funct Mater 2019; 29: 1807319. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Park C, Hahn JW. Metal-semiconductor-metal metasurface for multiband infrared stealth technology using camouflage color pattern in visible range. Adv Opt Mater 2022; 10: 2101930. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ergoktas MS, Bakan G, Kovalska E, et al. Multispectral graphene-based electro-optical surfaces with reversible tunability from visible to microwave wavelengths. Nat Photon 2021; 15: 493-498. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Gu J, Zhao T, et al. Tunable VO2 cavity enables multispectral manipulation from visible to microwave frequencies. Light Sci Appl 2024; 13: 54. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Wang X, Nong J, et al. Bicolor regulation of an ultrathin absorber in the mid-wave infrared and long-wave infrared regimes. ACS Photonics 2024; 11: 218-229. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Loke D, Lee TH, Wang WJ, et al. Breaking the speed limits of phase-change memory. Science 2012; 336: 1566-1569. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Amotchkina T, Trubetskov M, Hahner D, et al. Characterization of e-beam evaporated Ge, YbF3, ZnS, and LaF3 thin films for laser-oriented coatings. Appl Opt 2019; 59: A40-7. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Liu D, Chen D, et al. Transparent dynamic infrared emissivity regulators. Nat Commun 2023; 14: 5087. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Jiang T, Meng Y, et al. Scalable thermochromic smart windows with passive radiative cooling regulation. Science 2021; 374: 1501-1504. [Article] [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Z, Liu D, Pang Y, et al. Multispectral metal-based electro-optical metadevices with infrared reversible tunability and microwave scattering reduction. Nanophotonics 2024; 13: 3165-3174. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xi W, Liu Y, Zhao W, et al. Colored radiative cooling: How to balance color display and radiative cooling performance. Int J Therm Sci 2021; 170: 107172. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Liu Y, Xi W, et al. Colored radiative cooling: Progress and prospects. Mater Today Energy 2023; 34: 101302. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Yang J, Chen D, et al. Implementation of on-chip multi-channel focusing wavelength demultiplexer with regularized digital metamaterials. Nanophotonics 2020; 9: 159-166. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JD. Classical Electrodynamics. New York: Wiley, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Qin R, Ying Y, et al. Asymmetric directional control of thermal emission. Adv Mater 2023; 35: 2302478. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Heavens O. Thin-film optical filters. Optica Acta: Internat J Optics 1986; 33: 1336–1336 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Qiu M, Yu X, et al. Defining deep-subwavelength-resolution, wide-color-gamut, and large-viewing-angle flexible subtractive colors with an ultrathin asymmetric fabry-perot lossy cavity. Adv Opt Mater 2019; 7: 1900646. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Luo H, Zhu H, et al. Nonvolatile optically reconfigurable radiative metasurface with visible tunability for anticounterfeiting. Nano Lett 2021; 21: 5269-5276. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Zhang Z, Ma H, et al. Tunable mid-infrared selective emitter based on inverse design metasurface for infrared stealth with thermal management. Opt Express 2022; 30: 18250. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Shportko K, Kremers S, Woda M, et al. Resonant bonding in crystalline phase-change materials. Nat Mater 2008; 7: 653-658. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Palik ED. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids. Orlando: Academic Press, 1998 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Figure 1 The schematic of VIS-IR-LiDAR multispectral camouflage realized by simplified design for multi-scale regulation of structure and material. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2 (a) Optical transmission behavior in thin-film structure. (b) Color range and distribution of designed and experimental structure in CIE 1931 color space. (c) Photographs showcasing the fabricated structures with different thicknesses (NO.1: 65 nm; NO.2: 85 nm; NO.3: 120 nm; NO.4: 145 nm; NO.5: 180 nm; NO.6: 240 nm). (d) Experimental (Exp., solid line) and simulated (Sim., dotted line) reflectivity spectra of six structures within the visible waveband with color difference ({L-End}

|

| In the text | |

|

Figure 3 Reflectance spectra with different thicknesses of ZnS layer under crystalline (a) and amorphous (b) GST interlayers. (c) Electric field distribution of designed structure (NO.3) with marked skin depths at the resonant wavelength of 428 and 1064 nm. (d) Loss distribution of designed structure (NO.3) at the resonant wavelength. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 4 (a) Absorbance spectrum with different thicknesses of GST layer under crystalline state. (b) The calculated absorbance spectrum of the proposed metadevice. (c) Electric field distribution (left) and loss distribution (right) of designed structure at the resonant wavelength (10.6 μm). (d) Realization of adaptive thermal camouflage by modulating the phase state of GST. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 5 (a) SEM photograph of the fabricated metadevice. (b) The measured reflectance spectrum of the proposed metadevice with different stable heating temperatures. (c) Recording emittance (absorbance) of average emissivity in the LWIR band and CO2 laser wavelength of 10.6 μm. (d) Relationship between heat temperature and observed temperature with reference of grey-body with average emission of 0.3 and 0.9, respectively. (e) Outdoor analysis of observed temperature with versus heating temperature and average emission. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 6 (a) VIS camouflage evaluation and (b) MIR thermal camouflage evaluation of the proposed metadevice (NO.4 and NO.6) with references of different kinds of leaves. (c, d) LiDAR camouflage evaluation of the proposed metadevice for the different wavelengthes of 1.06 μm (NO.3 and without ZnS layer sample) and 10.6 μm (NO.5 with a-GST and c-GST). (e) Multispectral display with different bands version of VIS camera, laser detection, and MIR thermal camera. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.