| Issue |

Natl Sci Open

Volume 4, Number 6, 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 20250044 | |

| Number of page(s) | 19 | |

| Section | Materials Science | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1360/nso/20250044 | |

| Published online | 14 October 2025 | |

REVIEW

Zinc utilization rate in aqueous batteries: Regulation of interfacial thermodynamics and kinetics

Laboratory of Advanced Materials, Aqueous Battery Center, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Molecular Catalysis and Innovative Materials, Collaborative Innovation Center of Chemistry for Energy Materials, Shanghai Wusong Laboratory of Materials Science, College of Smart Materials and Future Energy, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China

* Corresponding authors (emails: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

(Min Wang); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

(Dongliang Chao))

Received:

11

September

2025

Revised:

12

October

2025

Accepted:

13

October

2025

Zinc-based aqueous batteries (ZABs) are promising candidates for grid-scale energy storage owing to zinc’s high theoretical capacity, inherent safety, environmental benignity, and low cost. However, their deployment is hindered by limited cycle life and insufficient energy density, primarily due to an inefficient zinc utilization rate (ZUR) and interfacial instability. Distinct from previous reviews that mainly survey material modifications, this work examines anode failure modes within a unified framework of interfacial thermodynamics and kinetics. We systematically elucidate how unfavorable thermodynamic barriers and kinetic limitations in ion transport and charge transfer synergistically trigger dendritic growth, corrosion, passivation, and mechanical pulverization, thereby constraining the ZUR. Building on these insights, we critically evaluate recent advances in electrolyte engineering, interfacial functionalization, and host design, with emphasis on their mechanisms for modulating nucleation thermodynamics and deposition kinetics. Finally, we propose actionable design principles that highlight the thermodynamic and kinetic balance as a prerequisite for durable, high-utilization zinc anodes, thereby translating fundamental insights into scalable, high-energy ZAB technologies.

Key words: aqueous batteries / zinc utilization rate / interfacial behavior / thermodynamics and kinetics

© The Author(s) 2025. Published by Science Press and EDP Sciences.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

INTRODUCTION

The rapid pace of global industrialization has led to a significant increase in energy demand, placing stringent requirements on energy storage technologies. Among various candidates, zinc-based aqueous batteries (ZABs) have emerged as a leading aqueous metal-ion system, primarily owing to their intrinsic safety and scalability. Their key advantages include low cost (~$3.2 kg−1), a favorable redox potential (−0.763 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)), high theoretical capacity (820 mAh g−1 and 5855 mAh cm−3), and the utilization of non-flammable aqueous electrolytes [1,2]. Consequently, ZABs are increasingly recognized as a promising alternative to lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) for next-generation large-scale energy storage.

Research on ZABs encompasses cathode materials (including manganese-based [3,4], vanadium-based [5–7], Prussian blue analogues [8,9], among others [10,11]), anodes, electrolytes, and their interactions, the performance and utilization of the anode critically govern key energy storage metrics such as energy density and cycling stability [12]. The functionality of zinc anodes fundamentally depends on the reversibility of Zn2+ plating/stripping electrochemistry [13]. Accordingly, considerable efforts have sought to maximize Coulombic efficiency (CE) toward its theoretical limit of 100%, ensuring the high reversibility required for practical applications. However, extended cycle life often comes at the expense of capacity and zinc utilization rate (ZUR), which is defined as the ratio of electrochemically active zinc participating in reversible reactions to the total amount of zinc present in the anode. For instance, Zn-Mn systems with a CE of 99% can cycle stably for over 458 cycles at low ZUR (<5%). However, such conditions underestimate dendritic failure risks that emerge at higher ZUR [14]. This highlights a critical trade-off, where high-ZUR exacerbates irreversible side reactions (e.g., hydrogen evolution, passivation) that deplete zinc reserves and accelerate capacity decay, while low ZUR yields full-cell energy densities far below theoretical predictions [15]. A substantial disparity persists between laboratory configurations, which are often characterized by low cathode loadings (~1–2 mg cm−2) and excessive zinc foil anodes (up to 1000 mg cm−2), and the balanced electrode designs required for commercial viability. Thus, the central challenge in metallic zinc anode engineering is to balance high-ZUR, which maximizes energy density, with long-term cycling stability, which ensures reliability (Figure 1). The interfacial thermodynamics and kinetics dictate this balance at the anode/electrolyte interface [16]. Unfavorable thermodynamics (e.g., high reactivity leading to spontaneous corrosion and hydrogen evolution) and kinetic limitations (e.g., sluggish Zn2+ desolvation or charge-transfer barriers) underpin irreversible side reactions and uneven zinc deposition, particularly under high-ZUR conditions [17,18]. Consequently, tailoring interfacial thermodynamics and kinetics is a key strategy to decouple high-ZUR from degradation pathways, thereby enabling durable, high-energy-density ZABs.

|

Figure 1 The balance of battery life and energy density at high-ZUR. |

This review comprehensively evaluates recent strategies to enhance the ZUR, linking fundamental challenges with corresponding mitigation strategies in ZABs. First, the interfacial electrodeposition mechanisms are analyzed from both thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives, with particular attention to deep-discharge anodes. The significant challenges associated with deep discharge (dendritic growth, corrosion, and mechanical degradation) are then identified and discussed. Next, strategies for achieving high ZUR are systematically categorized according to their primary interfacial regulation objectives, and representative influential studies are summarized. Finally, building on these insights, rational anode design principles are proposed with an emphasis on scalability and practical feasibility, facilitating the translation of laboratory advances into high-performance ZAB technologies.

CHALLENGES OF HIGH-ZUR

Low ZUR represents an inherent bottleneck to achieving high practical energy density in ZABs. To alleviate this, recent studies have commonly employed ultrathin zinc foils (<30 μm) as a practical approach to reducing anode mass. However, this strategy mitigates only the consequence of excessive parasitic mass, without addressing the root cause of low ZUR. Moreover, the fabrication of ultrathin foils is costly and technically challenging, while their limited mechanical strength compromises durability, rendering them highly susceptible to damage and deformation. This reliance on extreme foil thinning underscores the urgent need to redirect research efforts toward strategies that enhance intrinsic ZUR under realistic operating conditions.

In contrast, zinc powder anodes allow precise control of active material loading, thereby enabling systematic ZUR optimization. However, their large specific surface area exacerbates interfacial side reactions with aqueous electrolytes, and particle detachment during high-rate cycling generates electrically isolated dead zinc, which compromises reversibility and undermines long-term anode stability [19–21].

Fundamentally, metallic zinc is thermodynamically unstable in aqueous electrolytes because the equilibrium potential of the Zn2+/Zn redox couple (−0.763 V vs. SHE) is lower than that of the H+/H2 couple across the entire pH range. As a result, zinc anodes are prone to spontaneous corrosion accompanied by hydrogen evolution reactions (HER) [22]. Metallic impurities further aggravate this process by forming micro-galvanic cells at the anode/electrolyte interface, thereby accelerating electrochemical dissolution. This corrosion mechanism progressively degrades the electrode surface and increases interfacial impedance, ultimately limiting cycling stability. As illustrated in Figure 2a, zinc dissolution proceeds via anodic oxidation (Zn → Zn2+ + 2e−), while cathodic water reduction (2H2O + 2e− → H2↑ + 2OH−) generates gaseous H2 and alkaline OH− ions [23]. The accumulated hydrogen increases internal cell pressure, posing safety risks. Concurrently, hydroxide-induced precipitation of zincate species and the formation of anion-mediated passivation layers (e.g., Zn4SO4(OH)6·nH2O in ZnSO4 electrolytes) depositinsulating byproducts that impede charge transfer. Collectively, these degradation pathways induce irreversible self-discharge, kinetic hysteresis during plating/stripping, and reduced Coulombic efficiency (CE), thereby suppressing ZUR. Thin zinc foils (<30 μm) are particularly vulnerable under high-ZUR conditions, as their limited Zn2+ reservoirs cannot sustain prolonged operation, resulting in premature cell failure.

|

Figure 2 (a) Schematic diagrams of current challenges of high-ZUR anodes. (b) Modulate the interfacial field to exert a key influence on the negative electrode of ZABs. |

The electrode/electrolyte interface governs Zn2+ electrodeposition through a combination of coupled thermodynamic and kinetic factors (Figure 2b) [24]. Effective interfacial modulation is therefore essential to improve the ZUR [25]. Two interfacial failure modes are of primary concern.

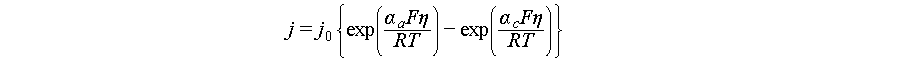

(1) Dendritic growth. Dendrite formation originates from the interplay of thermodynamic anisotropy and kinetic amplification. Thermodynamically, the zinc crystal exhibits significant anisotropy in deposition energy barriers, with certain crystallographic planes (particularly (002)) present with substantially lower barriers than others (e.g., (100), (101)) [26]. This preference drives nucleation and growth along low-energy orientations. Kinetically, morphological irregularities and local current density fluctuations intensify this bias. The resulting tip-enhanced electric field effect increases surface charge density at protrusions, further accelerating preferential deposition [27]. According to the Butler-Volmer relationship, even small increases in local overpotential can exponentially raise deposition rates, forming a self-reinforcing loop for dendrite growth [27]. Under high current densities, slow Zn2+ diffusion generates steep concentration gradients perpendicular to the electrode surface, exacerbating this instability. Dendritic structures also act as low-energy nucleation sites for secondary growth and may penetrate the separator, causing short circuits [28–30]. Moreover, dendrite breakage during cycling produces electrically isolated “dead zinc,” irreversibly consuming active material [12].

where j is the current density, j0 is the exchange current density, αa and αc are the anodic and cathodic charge transfer coefficients, F is the Faraday constant, η is the overpotential, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature.

(2) Mechanical pulverization. Repeated plating/stripping cycles, especially under high-rate deep-discharge conditions, induce mechanical pulverization. At high-ZUR, zinc preferentially deposits on low-energy-barrier sites (e.g., pre-existing nuclei or specific crystal planes), reflecting thermodynamic driving forces. However, kinetically limited mass transport (e.g., sluggish Zn2+ diffusion or desolvation) disrupts uniform ion supply, leading to localized and non-uniform deposition. The lack of a continuous, electronically and ionically conductive matrix further aggravates stress concentration and disrupts current homogeneity. As a result, localized growth combined with kinetic limitations gives rise to structural degradation, compromised electronic percolation, intensified polarization, and capacity fading due to active material detachment [31]. These predominant failure modes, dendritic growth driven by anisotropic thermodynamics and kinetically amplified non-uniformity, and pulverization arising from localized stress, originate from suboptimal interfacial thermodynamics and kinetics. Achieving high-ZUR, therefore, requires simultaneously minimizing interfacial energy barriers for uniform nucleation and ensuring fast ion transport/charge transfer kinetics for homogeneous deposition and effective stress dissipation. A deficiency in either domain critically hinders the durability of zinc anodes.

Beyond interfacial failure, cell-level architecture further limits practical ZUR performance. In coin cells, full-area contact between the anode and current collector maintains connectivity even with localized stripping or perforation. In contrast, pouch cells rely on localized tab welding; perforation near this restricted contact region rapidly isolates large anode areas from the circuit, rendering them electrochemically inactive well before bulk zinc consumption. Thus, optimizing electronic connectivity architecture under deep stripping is equally vital as suppressing dendrites and corrosion for achieving high-ZUR ZABs.

STRATEGIES FOR HIGH-ZUR

Interfacial instabilities, including corrosion, passivation, and dendrite growth, represent the primary bottlenecks limiting ZUR and battery durability in ZABs. To address these interfacial challenges rooted in unfavorable thermodynamics (high reactivity, anisotropic deposition barriers) and sluggish kinetics (mass transport limitations, charge transfer barriers), research strategies can be fundamentally categorized by their primary target of interfacial control. (1) Electrolyte component optimization: Modulating ion solvation structures, activity, and transport properties to alter deposition thermodynamics (nucleation overpotential) and kinetics (desolvation/ion mobility). (2) Functional interface layer modification: Designing functional interlayers to tune interfacial energy barriers (adsorption energies, tunneling probability) and local charge distribution, thereby steering nucleation pathways and deposition kinetics. (3) Host structural design: Constructing conductive scaffolds to homogenize nucleation sites (lowering local energy barriers) and accommodate plating/stripping-induced stress evolution, thereby enhancing mechanical stability.

This classification highlights that each strategy addresses distinct facets of interfacial thermodynamics or kinetic pathways. Together, they define the framework for balancing high-ZUR with long-term zinc anode durability.

Electrolyte component optimization

The solvation shell of Zn2+ in aqueous electrolytes plays a pivotal role in dictating zinc deposition and ZUR. The thermodynamics and kinetics of ion desolvation and subsequent interfacial processes primarily govern this behavior. In neutral to mildly acidic media, Zn2+ primarily exists as the hexaaquo complex [Zn(H2O)6]2+, stabilized by strong electrostatic ion-dipole interactions. However, the high desolvation energy barrier associated with this octahedral hydration structure results in significant kinetic challenges during electrodeposition [32]. Incomplete desolvation facilitates parasitic water splitting via co-reduction of coordinated H2O at the anode, generating by-products and consuming active zinc, thereby severely limiting ZUR. Strategies, particularly through the incorporation of coordinating additives, regulate Zn2+ solvation and interfacial reactions, enhancing ZUR via two pathways: surface adsorption that regulates ion distribution and in situ solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation that stabilizes the interface.

Reducing desolvation energy barrier: modifying the primary solvation shell to lower the activation energy required for Zn2+ desolvation. For instance, Sun et al. [33] demonstrated that glucose molecules in ZnSO4 electrolyte can thermodynamically displace one H2O ligand within the [Zn(H2O)6]2+ sheath. This substitution lowers the electrostatic potential, thereby reducing the desolvation energy barrier, kinetically inhibiting hydrogen evolution, corrosion, and by-product formation (Figure 3a). Glucose also adsorbs strongly on the anode, homogenizing the interfacial electric field to promote uniform deposition. Even at low concentration (10 mM), this thermodynamic/kinetic modulation significantly improved battery performance, implying better ZUR. Reconstructing solvation structure & forming protective SEI: utilizing additives that not only alter solvation but also form kinetic barriers. Wang et al. [34] employed N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) as a multifunctional additive. Beyond lowering desolvation barriers, electrolyte additives can simultaneously reconstruct the solvation environment and facilitate the formation of protective SEI layers. This SEI acts as a kinetic barrier, suppressing interfacial side reactions and facilitating efficient ion transport. The combined thermodynamic (solvation) and kinetic (SEI) effects enabled symmetrical cells to achieve an impressive 85.6% ZUR with stable operation for ≈200 h at 10 mAh cm−2, demonstrating superior reversibility under high-capacity conditions.

|

Figure 3 (a) Schematic illustration of the underlying mechanism of enhanced electrochemical performance by additive adsorption, which regulates Zn2+ solvation structure and promotes uniform ion distribution. (b) Schematic illustration of the in situ SEI formation mechanism, where controlled additive reduction generates a stable, ion-conductive, and electron-insulating interphase. |

Additives modulate interfacial kinetics by regulating the electric field and controlling nucleation at the interface. Li et al. [29] introduced high-valent cations (Ce3+, La3+). These cations preferentially adsorb at active nucleation sites, raising the local nucleation barrier and thereby redistributing deposition to less active regions. This forces zinc deposition to occur progressively at less active sites, shifting the mechanism from instantaneous to progressive nucleation. The resulting homogenized deposition kinetics lead to highly stable zinc stripping/plating behavior, enhancing ZUR stability. Zeng et al. [20] reported a strategy using Zn(H2PO4)2 as an additive. It reacts with OH− to form a dense, stable, and highly zinc-conductive SEI layer in situ. This SEI provides a kinetically favorable pathway for Zn2+ transport (ion conductivity: 7.2×10−5 S cm−1), while simultaneously kinetically suppressing side reactions, resulting in high reversibility and ZUR (Figure 3b). Engineering advanced SEI architectures: creating SEI structures designed for optimal kinetics. Meng et al. [35] formed an amorphous/crystalline bilayer SEI using a trace 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI) additive. The bilayer consisted of a ZnCO3-rich crystalline outer shell and a ZnS-rich amorphous inner region, which together enhanced kinetic stability and ion transport. This optimized interfacial kinetics enabled a Zn-Zn symmetric cell to achieve stable cycling for over 550 h under an extremely high areal capacity (28.4 mAh cm−2) and a record-high ZUR of 98% at 2 mA cm−2 (Figure 3b). These findings underscore electrolyte engineering as a powerful strategy to tune solvation thermodynamics and interfacial kinetics. By lowering energy barriers and establishing favorable ion transport pathways, such approaches suppress parasitic reactions and promote uniform, dense zinc deposition, thereby dramatically improving ZUR for practical ZABs.

Functional interface layer modification

The anode/electrolyte interfacial microenvironment plays a crucial role in determining the thermodynamics and kinetics of zinc deposition, as well as parasitic reactions, ultimately dictating the ZUR [36]. Functional coating engineering has emerged as a key strategy to optimize this interface by modulating both the interfacial electric field and concentration distribution (kinetic control) as well as surface energy (thermodynamic regulation). These coatings are classified as inorganic (Figure 4a), organic polymer (Figure 4b), and composite (Figure 4c) types. Such surface modifications effectively regulate ion transport pathways, lower nucleation overpotentials, promote uniform Zn2+ deposition, and suppress side reactions, thereby collectively enhancing the ZUR.

|

Figure 4 (a–c) Schematic illustration of zinc deposition on inorganic, organic polymer, and composite functional coatings, respectively, showing how different coating types guide Zn2+ transport, enhance interfacial stability, and enable uniform zinc deposition for improved reversibility. |

For instance, Ma et al. [37] constructed a dense and uniform ZnF2 insulating layer on the zinc foil through electrovalent bonding. ZnF2’s high dielectric constant and excellent ionic conductivity (80.2 mS cm−1) impart critical kinetic advantages by homogenizing the interfacial electric field and Zn2+ flux distribution. This homogenization reduces nucleation overpotentials, facilitates desolvation, and accelerates migration kinetics, thereby enabling highly uniform deposition. As a result, the Zn@ZnF2//Zn@ZnF2 symmetric cell maintained exceptional stability under ultrahigh current density and areal capacity (10 mA cm−2, 10 mAh cm−2) for more than 590 h, demonstrating superior ZUR even under extreme conditions. In addition, Yang et al. [38]. reported an unconventional strategy by depositing a 200 nm Cu coating on the backside of a 10 μm-thick zinc foil, contrary to conventional surface coatings. This design provides additional mechanical support, serves as a heat-transfer medium, and offers a reversible electronic pathway for zinc plating and stripping. Remarkably, the modified zinc anode achieved an 85.5% ZUR at 5 mA cm−2 and 5 mAh cm−2, significantly advancing the practical development of ZABs.

Polymeric coatings offer complementary advantages owing to their abundant polar functional groups, which can act as interfacial mediators through both thermodynamic and kinetic pathways. For example, Zhao et al. [39] employed a polyamide (PA) coating, in which the extensive hydrogen-bonding network interacts with coordinated water molecules in the [Zn(H2O)6]2+ solvation sheath. This interaction thermodynamically destabilizes the solvation structure and lowers the Zn2+ desolvation barrier. Simultaneously, strong coordination between PA’s amide groups and Zn2+ ions kinetically regulates nucleation density and facilitates uniform ion migration, even at high areal capacities (10 mAh cm−2). In addition, PA acts as a physical barrier that limits direct anode-electrolyte contact, thereby suppressing corrosion and passivation and further enhancing cycling stability (a practical indicator of ZUR). Similar interfacial regulation principles apply to other polymeric coatings such as polyvinyl butyral [40], polyimide [41], polyacrylamide, and polyvinylpyrrolidone (Figure 4b) [42].

Despite these advances, limitations remain. Inorganic coatings are susceptible to fracture under mechanical stress during cycling, while organic polymers may gradually dissolve in aqueous electrolytes, compromising long-term protection. To address these issues, researchers develop composite functional coatings that synergistically integrate inorganic and organic components. For example, Cui et al. [43] designed an organic-inorganic hybrid protective layer (Nafion-Zn-X) by incorporating Zn-X zeolite into the hydrophilic domains of Nafion. This architecture shifts ion migration pathways from solely through Nafion channels to the organic-inorganic interfaces, thereby achieving effective ion rectification. The rectification process homogenizes Zn2+ flux, while the Nafion component provides a low desolvation barrier and shields SO42− anions, collectively suppressing interfacial side reactions. The synergistic thermodynamic and kinetic regulation enables Zn@Nafion-Zn-X anodes to sustain deep plating/stripping (10 mAh cm−2) for more than 1000 h, representing one of the most durable demonstrations of high-ZUR to date.

Novel host structural design

Electrode structure design is a fundamental strategy for regulating the thermodynamics and kinetics of zinc deposition. By optimizing interfacial electric field and ion concentration distributions, this approach ultimately maximizes ZUR [44]. At high current densities (>10 mA cm−2), localized electric field intensification and sluggish Zn2+ migration exacerbate concentration polarization. These effects thermodynamically favor non-uniform deposition and parasitic reactions, severely reducing ZUR [45]. Three-dimensional (3D) electrodes, owing to their large surface area, provide an effective solution by homogenizing current distribution and mitigating concentration gradients (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5 (a) Schematic illustration of zinc deposition on zinc metal and alloy materials. (b) Schematic illustration of zinc deposition on inorganic materials. |

Guo et al. [46] developed a 3D nanoporous zinc electrode in which the interconnected pore structure kinetically ensures uniform current distribution and thermodynamically accommodates volume variation during cycling (Figure 5a). This dual optimization markedly enhanced ZUR and anode stability. The resulting symmetric cell exhibited outstanding cycling stability for > 200 h at a high depth of discharge (DOD) of 71%, directly demonstrating high-ZUR. Tian et al. [47] fabricated a 3D Zn-Mn alloy anode, whose alloy surface exhibited strong zinc-binding energy, thereby lowering the nucleation barrier and guiding uniform zinc deposition. The porous 3D framework further facilitated Zn2+ diffusion and deposition, kinetically suppressing dendrites and enabling efficient ZUR. Interfacial engineering can steer the crystallographic orientation of deposited zinc. Previous studies established that zinc preferentially grows along the zinc (002) facet to minimize interfacial energy [48]. Building on this principle, Zhang et al. [49] achieved dense, highly oriented (002) zinc films at current densities of 10–300 mA cm−2. This oriented growth not only delivered an impressive cumulative capacity > 2100 mAh cm−2 at 45.5% DOD, signifying high-ZUR, but also suppressed dendrites and hydrogen evolution.

Conductive carbon-based materials provide versatile scaffolds that primarily benefit kinetics (Figure 5b). For example, Zeng et al. [50] employed a 3D carbon nanotube (CNT) framework, which lowered nucleation overpotential and enabled dendrite-free deposition under deep discharge, indicative of improved ZUR. Similarly, 3D porous copper [51], carbon fiber [52], and MXene films [53] have been shown to homogenize the interfacial electric field, improving deposition uniformity. Du et al. [31] further fabricated binder-free zinc-graphene anodes, where graphene not only reduced polarization voltage (kinetic advantage) but also guided horizontal zinc deposition (thermodynamic benefit). As a result, full cells with this design achieved double the energy density of conventional foil anodes, demonstrating the promise of host engineering and powder processing in advancing ZUR. Despite these advantages, dense scaffolds such as CNTs can hinder ion diffusion, leading to preferential surface deposition. To overcome this bottleneck, Zhang et al. [54] developed a hybrid ion-electron conductor scaffold by incorporating ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) copolymer with CNT and zinc powder. EVA accelerated ion transport while CNT provided electronic conductivity, synergistically enhancing cycling stability and rate performance. This kinetic optimization directly improved the practical ZUR of high-loading zinc powder anodes.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

In summary, ZABs are promising for safe and low-cost energy storage, but their practical application is limited by poor cycle life and low energy density. These challenges mainly result from the low zinc utilization ratio, influenced by parasitic reactions and sluggish interfacial kinetics. To demonstrate feasibility, many laboratory studies adopt excess N/P ratios and electrolyte-rich configurations. While such practices temporarily alleviate failure modes, they thermodynamically mask the inherent instability of the anode/electrolyte interface and kinetically fail to resolve the fundamental transport and deposition limitations, ultimately sacrificing energy density and practical relevance. This review systematically examines the failure mechanisms of zinc anodes under high-ZUR conditions. It categorizes representative improvement strategies (summarized in Table 1) into three dimensions: (1) electrolyte component optimization; (2) functional interface layer modification; (3) host structural design. Herein, we provide critical opinions and actionable suggestions for developing practically viable zinc anodes that simultaneously achieve high-ZUR and long-term stability. We emphasize that future research must prioritize strategies offering concerted thermodynamic stabilization and kinetic enhancement at the anode/electrolyte interface.

Summary of improvement strategies for high utilization rate zinc anodes

Mechanistic elucidation and thermodynamic/kinetic optimization of zinc powder anodes

Current research on zinc anode design and theoretical frameworks has primarily concentrated on ultrathin zinc foils, whereas studies on zinc powder remain scarce. A critical knowledge gap persists in understanding the unique interfacial thermodynamics and kinetics of powder-based anodes. The nucleation behavior, deposition morphology, and parasitic reactions associated with powder surfaces remain poorly defined. Future studies should therefore emphasize fundamental investigations of surface reactions and local microenvironments in zinc powder systems. Key directions include clarifying how particle morphology, size distribution, and surface chemistry influence both thermodynamic stability and kinetic processes. Such mechanistic insights are indispensable for the rational design of zinc powder anodes that can concurrently achieve interfacial stabilization and kinetic enhancement at the particle level, thereby reducing voltage polarization and enabling stable, high-ZUR performance. In addition, zinc powder anodes, despite their high surface area and improved zinc utilization, present several practical challenges such as handling, oxidation, and mechanical instability. To address these issues, controlled fabrication, protective coatings, and the use of binders or conductive scaffolds are required to enhance electrode integrity and suppress side reactions. Overall, powder-based strategies are promising but must balance electrochemical activity with long-term durability and manufacturability.

Development of multifunctional separators for interfacial regulation

Beyond direct anode engineering, separators with tailored interfacial functionalities represent a promising but underexplored route to stabilize zinc anodes. Research in this area remains limited, with few studies explicitly targeting the anode/electrolyte interface through separator design. Future work should focus on creating multifunctional separators incorporating chemical groups or coatings that (i) thermodynamically passivate reactive sites or elevate energy barriers to parasitic reactions, and (ii) kinetically homogenize ion transport and guide uniform zinc deposition via selective interactions with Zn2+. Progress in such separator technologies, purposefully engineered for coupled thermodynamic and kinetic regulation, could play a pivotal role in advancing the commercialization of high-ZUR zinc batteries.

Establishment of practically relevant testing protocols for high-ZUR anodes

Bridging the gap between laboratory demonstrations and real-world deployment requires the adoption of more rigorous and practically relevant testing methodologies. This involves a two-pronged strategy comprising (i) longevity assessment through long-term cycling (e.g., > 1000 cycles) at lower, practical current rates (0.5–2 C) to reveal intrinsic stability and degradation mechanisms, and (ii) validation in relevant cell configurations beyond Zn-Zn symmetric cells, which primarily probes interfacial stability. Critical evaluation of zinc anode performance requires the use of Cu-Zn asymmetric cells to accurately assess nucleation barriers (first deposition process) and plating/stripping reversibility under practical N/P ratios. In addition, full-cell configurations employing high areal capacity cathodes (> 2 mAh cm−2) and lean electrolytes are needed to evaluate system-level energy density and ZUR. For high-ZUR anodes, maintaining a ZUR of approximately 70%–85% under realistic conditions, including N/P ratios of about 1–3 and electrolyte volumes of 10–30 μL (mAh)−1, is considered most promising for promoting the practical application of ZABs.

Adopting such protocols is essential to accurately benchmark the actual effectiveness of emerging strategies, ensuring that thermodynamic stabilization and kinetic enhancement translate into practically relevant, high-ZUR zinc anodes.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFE0101100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A2060, 22088101, 22279023, 22309031), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20720250005), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (22JC1410200, 25PY2600100, 2024ZDSYS02, 25DZ3002901), the Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan Morning Star Project (23YF1401800), and the Shanghai Pilot Program for Basic Research–Fudan University 21TQ1400100 (25TQ012). The authors also thank the AI for Science Foundation of Fudan University (FudanX24A1035) and the National Research Foundation, Singapore, under its Singapore-China Joint Flagship Project (Clean Energy) for the support.

Author contributions

Z.W., J.C., and Z.Y. wrote the manuscript and edited the manuscript. Y.L. and S.L. reviewed the formal analysis. W.Z. reviewed the manuscript. M.W. and D.C. supervised the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang Y, Liu C, Lv Z, et al. Synergistic manipulation of Zn2+ ion flux and desolvation effect enabled by anodic growth of a 3D ZnF2 matrix for long‐lifespan and dendrite‐free Zn metal anodes. Adv Mater 2021; 33: 2007388. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Borodin O, Gao T, et al. Highly reversible zinc metal anode for aqueous batteries. Nat Mater 2018; 17: 543-549. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Yang Y, Liang S, et al. pH‐buffer contained electrolyte for self-adjusted cathode-free Zn-MnO2 batteries with coexistence of dual mechanisms. Small Struct 2021; 2: 2100119. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Zou L, Liu L, et al. Joint charge storage for high-rate aqueous zinc-manganese dioxide batteries. Adv Mater 2019; 31: 1900567. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Chao D, Zhu CR, Song M, et al. A high-rate and stable quasi-solid-state zinc-ion battery with novel 2D layered zinc orthovanadate array. Adv Mater 2018; 30: 1803181. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Huang Z, Kalambate PK, et al. V2O5 nanopaper as a cathode material with high capacity and long cycle life for rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion battery. Nano Energy 2019; 60: 752-759. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Li F, Gao J, et al. Additive‐free ultrastable hydrated vanadium oxide sol/carbon nanotube ink for durable and high‐power aqueous zinc‐ion battery. Adv Mater Inter 2022; 9: 2200174. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Nai J, Lou XWD. Hollow structures based on prussian blue and its analogs for electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Adv Mater 2019; 31: 1706825. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Mo F, Liu Z, et al. Activating C‐coordinated iron of iron hexacyanoferrate for Zn hybrid‐ion batteries with 10000‐cycle lifespan and superior rate capability. Adv Mater 2019; 31: 1901521. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G, Liang S, Chen Z, et al. Simultaneous cationic and anionic redox reactions mechanism enabling high‐rate long‐life aqueous zinc‐ion battery. Adv Funct Mater 2019; 29: 1905267. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Chen S, Li H, et al. Initiating a mild aqueous electrolyte Co3O4/Zn battery with 2.2 V-high voltage and 5000-cycle lifespan by a Co(III) rich-electrode. Energy Environ Sci 2018; 11: 2521-2530. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Luan J, Tang Y, et al. Interfacial design of dendrite‐free zinc anodes for aqueous zinc‐ion batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020; 59: 13180-13191. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ma L, Han C, et al. Advanced rechargeable zinc-based batteries: Recent progress and future perspectives. Nano Energy 2019; 62: 550-587. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Ang EH, Yang Y, et al. Challenges in the material and structural design of zinc anode towards high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2020; 13: 3330-3360. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Zhuang P, Zhang X, et al. Strategies for dendrite‐free anode in aqueous rechargeable zinc ion batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2020; 10: 2001599. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Wang J, Lu Z, et al. Ultrafast metal electrodeposition revealed by in situ optical imaging and theoretical modeling towards fast‐charging Zn battery chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed 2022; 61: e202116560. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A, Roy K, Heil JN, et al. Realizing the kinetic origin of hydrogen evolution for aqueous zinc metal batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2024; 14: 2402521. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Xie X, Ruan P, et al. Thermodynamics and kinetics of conversion reaction in zinc batteries. ACS Energy Lett 2024; 9: 2037-2056. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wang Y, Mo F, et al. Calendar life of Zn batteries based on Zn anode with Zn powder/current collector structure. Adv Energy Mater 2021; 11: 2003931. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Mao J, Hao J, et al. Electrolyte design for in situ construction of highly Zn2+‐conductive solid electrolyte interphase to enable high‐performance aqueous Zn‐ion batteries under practical conditions. Adv Mater 2021; 33: 2007416. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Luo Y, Qi B, et al. Interfacial engineering regulates deposition kinetics of zinc metal anodes. ACS Appl Energy Mater 2021; 4: 11743-11751. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lu X, Lai F, et al. Rechargeable aqueous Zn-based energy storage devices. Joule 2021; 5: 2845-2903. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Bayaguud A, Fu Y, Zhu C. Interfacial parasitic reactions of zinc anodes in zinc ion batteries: Underestimated corrosion and hydrogen evolution reactions and their suppression strategies. J Energy Chem 2022; 64: 246-262. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Dong N, Zhang F, Pan H. Towards the practical application of Zn metal anodes for mild aqueous rechargeable Zn batteries. Chem Sci 2022; 13: 8243-8252. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Zhang S, Hong H, et al. Interface regulation and electrolyte design strategies for zinc anodes in high-performance zinc metal batteries. iScience 2025; 28: 111751. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Liang G, Guo Y, et al. Do zinc dendrites exist in neutral zinc batteries: A developed electrohealing strategy to in situ rescue in‐service batteries. Adv Mater 2019; 31: 1903778. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell DA. Quantitative phase-field modeling of dendritic electrodeposition. Phys Rev E 2015; 92: 011301. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Li Q, Liu Z, et al. Dendrites in Zn‐based batteries. Adv Mater 2020; 32: 2001854. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wu P, Zhong W, et al. A progressive nucleation mechanism enables stable zinc stripping-plating behavior. Energy Environ Sci 2021; 14: 5563-5571. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Zhang X, Wang T, et al. Interfacial engineering strategy for high-performance Zn metal anodes. Nano-Micro Lett 2022; 14: 6. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Huang S, Zhang Y, et al. Enable commercial Zinc powders for dendrite-free zinc anode with improved utilization rate by pristine graphene hybridization. Energy Storage Mater 2022; 45: 465-473. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Li S, Hou R, et al. Recent advances in zinc-ion dehydration strategies for optimized Zn-metal batteries. Chem Soc Rev 2024; 53: 7742-7783. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Ma L, Zhou W, et al. Simultaneous regulation on solvation shell and electrode interface for dendrite‐free Zn ion batteries achieved by a low‐cost glucose additive. Angew Chem 2021; 133: 18395-18403. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Lv D, Liu H, et al. In situ formation of nitrogen‐rich solid electrolyte interphase and simultaneous regulating solvation structures for advanced Zn metal batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2022; 61: e202212839. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Wang M, Wang J, et al. Robust bilayer solid electrolyte interphase for Zn electrode with high utilization and efficiency. Nat Commun 2024; 15: 8431. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Dai S, Zhu Z, et al. Crystal water boosted Zn2+ transfer kinetics in artificial solid electrolyte interphase for high-rate and durable Zn anodes. ACS Appl Energy Mater 2022; 5: 10581-10590. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Li Q, Ying Y, et al. Toward practical high‐areal‐capacity aqueous zinc‐metal batteries: Quantifying hydrogen evolution and a solid‐ion conductor for stable zinc anodes. Adv Mater 2021; 33: 2007406. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Gao Y, Bu F, et al. Backside coating for stable Zn anode with high utilization rate. Adv Mater 2024; 36: 2312934. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Zhao J, Hu Z, et al. Long-life and deeply rechargeable aqueous Zn anodes enabled by a multifunctional brightener-inspired interphase. Energy Environ Sci 2019; 12: 1938-1949. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Li X, Zhang S, et al. Designing dendrite‐free zinc anodes for advanced aqueous zinc batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2020; 30: 2001263. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Hu J, Lu Q, et al. A patternable and in situ formed polymeric zinc blanket for a reversible zinc anode in a skin‐mountable microbattery. Adv Mater 2021; 33: 2007497. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Deng W, Li C, et al. Uniformizing the electric field distribution and ion migration during zinc plating/stripping via a binary polymer blend artificial interphase. J Mater Chem A 2020; 8: 17725-17731. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Zhao Q, Wu X, et al. An interface‐bridged organic-inorganic layer that suppresses dendrite formation and side reactions for ultra‐long‐life aqueous zinc metal anodes. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020; 59: 16594-16601. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SB, Ran Q, Yao RQ, et al. Lamella-nanostructured eutectic zinc-aluminum alloys as reversible and dendrite-free anodes for aqueous rechargeable batteries. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 1634. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z, Chen G, Hou F, et al. Strategies for the stabilization of Zn metal anodes for Zn‐ion batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2021; 11: 2003065. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Cong Z, Guo Z, et al. Dendrite-free Zn anode with dual channel 3D porous frameworks for rechargeable Zn batteries. Energy Storage Mater 2020; 30: 104-112. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Li Z, Feng G, et al. Stable, high-performance, dendrite-free, seawater-based aqueous batteries. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 237. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Zhao Q, Tang T, et al. Reversible epitaxial electrodeposition of metals in battery anodes. Science 2019; 366: 645-648. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Huang W, Li L, et al. Nonepitaxial electrodeposition of (002)‐textured Zn anode on textureless substrates for dendrite‐free and hydrogen evolution‐suppressed Zn batteries. Adv Mater 2023; 35: 2300073. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Zhang X, Qin R, et al. Dendrite‐free zinc deposition induced by multifunctional CNT frameworks for stable flexible Zn‐ion batteries. Adv Mater 2019; 31: 1903675. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Yang H, Wang X, et al. Enabling stable Zn anode via a facile alloying strategy and 3D foam structure. Adv Mater Inter 2021; 8: 2002184. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Shi JL, Wang TS, et al. 3D zinc@carbon fiber composite framework anode for aqueous Zn-MnO2 batteries. RSC Adv 2018; 8: 19157-19163. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, An Y, Wei C, et al. Flexible and free-standing Ti3C2Tx MXene@Zn paper for dendrite-free aqueous zinc metal batteries and nonaqueous lithium metal batteries. ACS Nano 2019; 13: 11676-11685. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Yu P, Xiong K, et al. Construction of mixed ionic‐electronic conducting scaffolds in Zn powder: A scalable route to dendrite‐free and flexible Zn anodes. Adv Mater 2022; 34: 2200860. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, Tan H, Gao Y, et al. Tailoring desolvation kinetics enables stable zinc metal anodes. J Mater Chem A 2020; 8: 19367-19374. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Pollard TP, Zhang Y, et al. Functionalized phosphonium cations enable zinc metal reversibility in aqueous electrolytes. Angew Chem 2021; 133: 12546-12553. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ma J, Meng Y, et al. High‐capacity zinc anode with 96 % utilization rate enabled by solvation structure design. Angew Chem Int Ed 2023; 62: e202214966. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Jin H, Xie K, et al. Molecular‐level Zn‐ion transfer pump specifically functioning on (002) facets enables durable Zn anodes. Small 2022; 18: 2204713. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Wang H, Du H, et al. Lanthanum nitrate as aqueous electrolyte additive for favourable zinc metal electrodeposition. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 3252. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Zhao X, Liu S, et al. Stabilizing zinc anodes by regulating the electrical double layer with saccharin anions. Adv Mater 2021; 33: 2100445. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, Tang Z, Han B, et al. Regulating inorganic and organic components to build amorphous‐ZnFx enriched solid‐electrolyte interphase for highly reversible Zn metal chemistry. Adv Mater 2023; 35: 2210051. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Xu L, Zhou Y, et al. Regulating the inner helmholtz plane with a high donor additive for efficient anode reversibility in aqueous Zn‐ion batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2023; 62: e202302302. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Zhao J, Hu W, et al. Regulating interfacial ion migration via wool keratin mediated biogel electrolyte toward robust flexible Zn‐ion batteries. Small 2022; 18: 2107163. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, Cui C, Zhang K, et al. A non-flammable hydrous organic electrolyte for sustainable zinc batteries. Nat Sustain 2022; 5: 205-213. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wang Z, Sun W, et al. Regulating interface engineering by helmholtz plane reconstructed achieves highly reversible zinc metal anodes. Adv Mater 2025; 37: 2420489. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Jiao Y, Wu P. Guiding Zn uniform deposition with polymer additives for long‐lasting and highly utilized Zn metal anodes. Angew Chem Int Ed 2023; 62: e202314456. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K, Li Z, Qiu X, et al. Boosting Zn anode utilization by trace iodine ions in organic‐water hybrid electrolytes through formation of anion‐rich adsorbing layers. Angew Chem Int Ed 2023; 62: e202309594. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Chen W, Yang Y, et al. A dual salt/dual solvent electrolyte enables ultrahigh utilization of zinc metal anode for aqueous batteries. Adv Mater 2024; 36: 2405889. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Pan Y, Jiao Y, et al. α-Methyl group reinforced amphiphilic poly(ionic liquid) additive for high‐performance zinc-iodine batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2025; 64: e202423326. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ma J, Meng Y, et al. In situ formation of solid electrolyte interphase facilitates anode-free aqueous zinc battery. eScience 2025; 5: 100397. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Feng X, Li M, et al. Overcoming challenges: Extending cycle life of aqueous zinc‐ion batteries at high zinc utilization through a synergistic strategy. Small 2024; 20: 2308273. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wang X, Ke J, et al. Approaching 100% comprehensive utilization rate of ultra‐stable Zn metal anodes by constructing chitosan‐based homologous gel/solid synergistic interface. Adv Funct Mater 2024; 34: 2313150. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Li H, Sun X, et al. Minimizing Zn loss through dual regulation for reversible zinc anode beyond 90% utilization ratio. Small 2025; 21: 2411986. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Wu G, Zhu R, et al. Synergistic cation solvation reorganization and fluorinated interphase for high reversibility and utilization of zinc metal anode. ACS Nano 2023; 17: 25335-25347. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Li F, Jin X, et al. Engineering polymer glue towards 90% zinc utilization for 1000 hours to make high‐performance Zn‐ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2021; 31: 2107652. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P, Zhou X, Wei A, et al. Fast‐charging and ultrahigh‐capacity zinc metal anode for high‐performance aqueous zinc‐ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2021; 31: 2100398. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Kim H, Kim W, et al. Water-repellent ionic liquid skinny gels customized for aqueous Zn-ion battery anodes. Adv Funct Mater 2021; 31: 2103850. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Dong N, Zhao X, Yan M, et al. Synergetic control of hydrogen evolution and ion-transport kinetics enabling Zn anodes with high-areal-capacity. Nano Energy 2022; 104: 107903. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Dai S, Xie K, et al. Regulating interfacial desolvation and deposition kinetics enables durable Zn anodes with ultrahigh utilization of 80%. Small 2022; 18: 2106441. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Yang Y, Liu G, et al. Redirected Zn electrodeposition by an anti‐corrosion elastic constraint for highly reversible Zn anodes. Adv Funct Mater 2021; 31: 2001867. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Nie C, Wu X, et al. Ion sieve interface assisted zinc anode with high zinc utilization and ultralong cycle life for 61 Wh/kg mild aqueous pouch battery. ACS Nano 2024; 18: 5003-5016. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Woottapanit P, Geng S, et al. Highly reversible Zn anode design through oriented ZnO(002) facets. Adv Mater 2024; 36: 2408908. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Xiao J, Xiao X, et al. Molecular engineering of self-assembled monolayers for highly utilized Zn anodes. eScience 2024; 4: 100205. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Duan F, Yin X, Ba J, et al. A hydrophobic and zincophilic interfacial nanofilm as a protective layer for stable Zn anodes. Adv Funct Mater 2024; 34: 2310342. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Zhong Y, tan P, et al. Thickness‐controlled synthesis of compact and uniform mof protective layer for zinc anode to achieve 85% zinc utilization. Small 2023; 19: 2302161. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- La S, Gao Y, Cao Q, et al. A thermal transfer-enhanced zinc anode for stable and high-energy-density zinc-ion batteries. Matter 2025; 8: 102013. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, Zhu J, Yan B, et al. Gradient fluorinated alloy to enable highly reversible Zn-metal anode chemistry. Energy Environ Sci 2022; 15: 1086-1096. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Zhong X, Zhang Q, et al. An extended substrate screening strategy enabling a low lattice mismatch for highly reversible zinc anodes. Nat Commun 2024; 15: 753. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Liao X, Xu W, et al. Ion selective and water resistant cellulose nanofiber/MXene membrane enabled cycling Zn anode at high currents. Adv Energy Mater 2023; 13: 2300283. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Cheng Z, Li Z, et al. Rational design of zinc powder anode with high utilization and long cycle life for advanced aqueous Zn-S batteries. Mater Horiz 2023; 10: 2436-2444. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Yang N, Bu F, et al. Double-sided engineering for space-confined reversible Zn anodes. Energy Environ Sci 2024; 17: 1894-1903. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wang X, Shen X, et al. 3D confined zinc plating/stripping with high discharge depth and excellent high-rate reversibility. J Mater Chem A 2020; 8: 11719-11727. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan D, Zhao J, Ren H, et al. Anion texturing towards dendrite‐free Zn anode for aqueous rechargeable batteries. Angew Chem 2021; 133: 7289-7295. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Huang J, Guo Z, et al. A metal-organic framework host for highly reversible dendrite-free zinc metal anodes. Joule 2019; 3: 1289-1300. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Yang F, Xu W, et al. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks as Zn2+ modulation layers to enable dendrite‐free Zn anodes. Adv Sci 2020; 7: 2002173. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Huang W, Guo W, et al. Sn alloying to inhibit hydrogen evolution of Zn metal anode in rechargeable aqueous batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2022; 32: 2108533. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Zhang S, Chu Y, et al. Stacked lamellar matrix enabling regulated deposition and superior thermo‐kinetics for advanced aqueous Zn‐ion system under practical conditions. Adv Funct Mater 2021; 31: 2107397. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Luan J, Fu L, et al. The three‐dimensional dendrite‐free zinc anode on a copper mesh with a zinc‐oriented polyacrylamide electrolyte additive. Angew Chem Int Ed 2019; 58: 15841-15847. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S, Zhou D, Jiang Y, et al. Lightweight Zn‐philic 3D‐Cu scaffold for customizable zinc ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2024; 34: 2312664. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wang H, Yu H, et al. Engineering an ultrathin and hydrophobic composite zinc anode with 24 μm thickness for high‐performance Zn batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2023; 33: 2303466. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lin Q, Zheng Z, et al. How is cycle life of three-dimensional zinc metal anodes with carbon fiber backbones affected by depth of discharge and current density in zinc-ion batteries?. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022; 14: 12323-12330. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Guo B, Chen Y, et al. High zinc utilization aqueous zinc ion batteries enabled by 3D printed graphene arrays. Energy Storage Mater 2023; 54: 75-84. [Article] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Figure 1 The balance of battery life and energy density at high-ZUR. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2 (a) Schematic diagrams of current challenges of high-ZUR anodes. (b) Modulate the interfacial field to exert a key influence on the negative electrode of ZABs. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 3 (a) Schematic illustration of the underlying mechanism of enhanced electrochemical performance by additive adsorption, which regulates Zn2+ solvation structure and promotes uniform ion distribution. (b) Schematic illustration of the in situ SEI formation mechanism, where controlled additive reduction generates a stable, ion-conductive, and electron-insulating interphase. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 4 (a–c) Schematic illustration of zinc deposition on inorganic, organic polymer, and composite functional coatings, respectively, showing how different coating types guide Zn2+ transport, enhance interfacial stability, and enable uniform zinc deposition for improved reversibility. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 5 (a) Schematic illustration of zinc deposition on zinc metal and alloy materials. (b) Schematic illustration of zinc deposition on inorganic materials. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.